INTRODUCTION

The Power of Difference Model is a tool for understanding how power and our sociocultural differences of race, ethnicity, culture, language, gender, nationality, size, religion/spirituality, ability/disability, sexual orientation, age, and socioeconomic status work within us (internally), between us (in relationships), and in our structures and institutions. The model goes beyond cognitive understanding to offer a map for “leveraging” (utilizing and/or integrating) this power non-violently in service to equity, inclusivity, and social justice.

Intrapersonally, interpersonally, organizationally, and institutionally, the PDM helps us to know and engage who we are, where we want to go, and shows us how to get there. In our experience, at The Sum, as we learn these skills we are able to unleash our own unique gifts in fulfilling and satisfying ways, aligning with and empowering processes that support vibrant, sustainable lives, organizations, and communities.

Our human sociocultural locations/identities are salient parts of our lives and societies, whether or not we are conscious of them and how they are at work. Experiences with family, cultures, institutions (school, government, media, etc.), and our own sociocultural locations, continually expose us to rules of institutional/structural power across difference. These power rules are structured to determine who gets to be on the top, how to get there, how to stay there, who is championed, sanctioned, dismissed, discarded, and who gets to make the rules. The rules are communicated explicitly and implicitly, consciously and unconsciously, verbally and nonverbally. They have come to all of us across a long history that, each day, comes present in our personal and institutional lives, both in past as well as updated mutated forms.

These rules manifest intrapersonally and interpersonally. They are enacted and perpetuated institutionally through policies, practices, and procedures that advantage some and discriminate against others. They are authorized and infused throughout every aspect of society by structurally normalizing and legitimizing the granting of power, privilege, and supremacy to some, while others are systematically, cumulatively marginalized and oppressed based on sociocultural location.

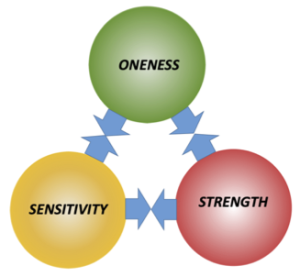

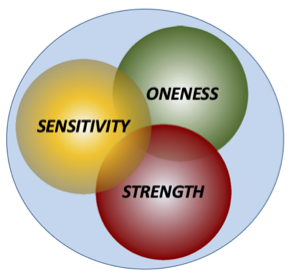

Within this ongoing context, we develop patterns of relating to and managing institutional/structural power. We are often unaware of these patterns, but they are observable in the way we feel and think, in the narratives we speak, and in how we react to human sociocultural difference. The Power of Difference Model describes three primary patterns, or “power perspectives,” — Sensitivity, Strength, and Oneness.

We may predominantly value and respond from different power perspectives in relationship to different sociocultural locations. For example, we may primarily hold the Strength power perspective in relationship to gender and the Sensitivity power perspective in relationship to socioeconomic class.

Each power perspective provides benefits to the person or organization that values it and, it also comes with liabilities. These liabilities emanate from the insufficiency of each perspective by itself. Whichever perspective we value, the other two locations are often perceived only in terms of their liabilities that appear to be in opposition. In our experience, these power perspectives actually function interdependently. Deep knowledge of our primary power perspective (its benefits and liabilities) AND the leveraging of aspects of the other perspectives catalyze effective functioning of the whole person, relationship, group, organization, or institution. This leveraging is essential to our developing the capacity to act in deeply democratic ways, impacting others in alignment with our intentions. It allows us to honor ourselves, our differences, to serve our common humanity, and to find a fulfilling relationship with power that is non-violent and mutually empowering to all. Through the leveraging of all three power perspectives, we can begin to cultivate just, sustainable, and thriving communities, organizations, and systems on every level: internally, socially, economically, technologically, and environmentally.

In our experience, our ability to leverage all three power perspectives occurs naturally if/when we are given supported, personalized learning opportunities. Creating and delivering these opportunities is the purpose of The Sum.

BACKGROUND

The Power of Difference Model was developed as a result of three primary observations we, at The Sum, made over many years of exploring other models that addressed how individuals and groups relate to sociocultural differences.

The Crossroads of POWER AND DIFFERENCE

First, we noticed that, in a number of models, sociocultural differences were addressed solely, or primarily, with a “horizontal” focus–difference as just difference. These differences were wonderful and fascinating to explore, and it was crucial that they be brought to awareness. Yet, in our work, we had found that it was the “vertical” focus–the power infused dynamics of difference–that carried the most profound impact on ourselves and the individuals and groups with whom we were working. Oppression, supremacy, unconscious privilege, white “fragility”, “battle fatigue”, internalized violence…all get acted out within this vertical aspect of sociocultural difference. Power is, in our experience, most often, the “elephant in the room.” By explicitly naming and addressing power personally and structurally, we engage with areas of deepest challenge and opportunity that hold the most potential for healing, transformation, and creativity with regard to sociocultural difference.

DIFFERENT DIFFERENCES

Our second observation was that some models that addressed issues of power and difference focused on only one sociocultural location (e.g. culture or sexual orientation). In our work, we needed and wanted a tool that encompassed a broader perspective. Our work with individuals and groups had taught us that inclusion of numerous sociocultural locations more accurately reflects reality, and that increasing capacity in one location could actually create the conditions for greater incapacity with regard to another sociocultural location! We organized a model that explored and articulated these complex intersectional dynamics that exist within us, in our relationships, and institutions. While recognizing the unique expressions of oppression and supremacy associated with each specific sociocultural location, we have also found it valuable to explore the patterns that appear to be present across these different locations.

MODEL PATRIARCHY/HIERARCHY

Our third observation was that most models examining sociocultural differences have a developmental stage or worldview structure. These models often use “polite” terms for individuals on one end of a spectrum who “don’t get it” and those on the other end who “do get it.” We found that this creates a hierarchy that can, beyond simply describing an aspect of reality, actually reproduce the unwanted uses of power that we are ultimately attempting to transform! We began asking what a model might look like if it did not embody or re-enact this kind of hierarchy.

The POWER PERSPECTIVES

SENSITIVITY

Those of us who predominantly hold the power perspective of Sensitivity tend to value sociocultural differences. We recognize and acknowledge the spectrum of human differences within and between us and ally ourselves with these differences. We begin to recognize the places where we have institutional/structural privilege, as well as the places where we are marginalized, and how both impact us internally. We are becoming invested in considering how oppression impacts others in our relationships and in the broader society, and in examining our personal investment in supremacy. We tend to enjoy learning, practicing, and applying specific socioculturally diverse “codes” in service to personal relationship building across difference, knowledge acquisition, and a quenching of intellectual and/or academic curiosity about how power functions within and across institutions. We may experience these aspects of Sensitivity as expansive and exciting.

When we hold the power perspective of Sensitivity as primary, we may also experience valuing of difference as overwhelming. Our burgeoning awareness of the power of oppression and our desire to value and include all differences equally (a kind of ethical relativism) can create an internal impasse resulting in some emotional and physical frozenness. We may lose track of our developing ability and willingness to be decisive in thought and action, having difficulty setting boundaries and saying “no” to prejudice, discrimination, and/or oppression intrapersonally, interpersonally, and institutionally/structurally.

Sensitivity Day In and Day Out

This power perspective may have an intellectual quality that is not yet integrated with managing feelings that arise in the face of oppression. Thus, we may find it difficult to respond fluidly or in the moment. We may lack effective resilience, stability, and clarity. Sensitivity can lead to a sense of underlying hopelessness and exhausted energy. Consequently, we may feel overwhelmed by others, especially by those who primarily value the Strength power perspective. The dynamics of this power perspective may lead us to keep these feelings and concerns to ourselves, creating a sense of aloneness and isolation. Underneath, we may have a strong drive to change people, to “get them to get it,” believing that only then will we be able to “breathe.”

Holding the sensitivity power perspective our internal and external narrative may be: “If only we could get ____________ to do this workshop” or “We need to welcome all perspectives and several people said they don’t like this diversity initiative, so what should we do?” or “I don’t want to offend anyone, so I’m not sure what to do or say.”

Sensitivity—Our Leveraging Work

When we hold the Sensitivity power perspective, it is essential that we learn about the dynamics of systemic power, privilege, and supremacy within systems and between people, but especially within us. We must come to know that “we are the change we want to see in the world.” We must come to recognize and shift our focus off of “getting others to get it” or imagining that only this change in others will create meaningful change in the world. It is critical that we have modeling and guidance from those who possess these skills. In this way, we can develop tools to recognize and manage a wide range of feelings, seek necessary support, and work with feelings as tools for self-care. Following are some ways that leveraging aspects of Strength and Oneness can support us in this process.

Our primary learning edge, challenge, and opportunity is to leverage/integrate/utilize Strength in a way that is non-violently loving. This shift must occur within our body and mind. It requires on-going practice that cultivates frames and feelings that allow us to be self-resourced (not dependent on the actions/feelings of others) over time, and in the moment, as we face internal and external oppression. This learning requires that we consciously make choices that are non-violent to ourselves and to others. Our self-resourcing and disruption of oppression can then become both ferocious and caring in service. It requires that we make an ongoing commitment to severing how we use power from the long-held systems of oppression that are channeled through individuals and institutions.

A secondary learning edge, challenge, and opportunity is to leverage/integrate/utilize the desire for connection that is central to Oneness, combining it with our burgeoning awareness of how our privilege, power, and marginalization work within and between us. The focus on connection can offer much with which to address the sense of isolation and aloneness that can exist as core experiences of the Sensitivity power perspective. This aspect of Oneness can provide the impetus to remember to work to find points of contact with others (particularly those who hold the Strength perspective) while our deepened understanding of oppression can provide the tools and impetus to develop the skills that make those contacts more authentic and mutually supportive within, and across, sociocultural difference. Finally, as we choose to stay awake to the violence and suffering that we as humans can and do enact and experience through oppression, the awareness of humanness held in Oneness can provide us with oxygen to breathe as we do that critical work.

Relationship to Difference: Deep Value

Law: Platinum Rule (treat others the way they would like to be treated)

Safety comes from: Getting others to “get it.”

Identity: Open-Mindedness

Truth: Subjective

Body Location: Head

Archetypal Representation: Magician

STRENGTH/APPRECIATION

Those of us who predominantly hold the power perspective of Strength tend to evaluate difference with a high level of conviction. We see human differences as superior or inferior and we assume that we are qualified to make these determinations. We may view others’ differences as less significant or less “real” than our own, and experience openness to the legitimacy of others’ difference as a threat to me/us and my/our legitimacy. As a result, faced with significant differences, we may act to minimize, disrupt, or remove them. One way that we may do so is by vilifying the qualities of those differences and the individuals who embody them, while espousing the virtues and contributions of our own individual and our own group’s members, ways of being, and sensibilities. This process may occur through stories of the history of our own and others’ groups, focusing on the virtues of the former and the flaws and pathologies of the latter.

The stories/narratives may become tied to, and support, the feelings that we express when we hold this power perspective as primary, especially when topics and issues of difference are raised. In that context, we will view ourselves as embodying drive, leadership, decisiveness, clarity, energy, and even ferociousness. We may also feel, act, and be experienced by others as judgmental, defensive, angry, and combative. We may, consciously or unconsciously, fear that valuing differences will result in ourselves or our own group being devalued, compromised, dismissed, forgotten, and/or obliterated

Sometimes this power perspective can present in an inverse form in which we appreciate a sociocultural difference, but tend to over-focus on, objectify, and romanticize it. This can be and can have the appearance of appropriation and is often offensive to those whose difference is being appropriated.

Strength Day In and Day Out

The ongoing experience when we hold this power perspective as primary may be one of frustration, worry that what we cherish as core to existence will be taken away, and of urgency, intensity, and great concern about the consequences of not being understood or valued. This latter issue is especially salient because this dynamic can be coded as danger and isolation. We may also experience rage associated with the belief that we are entitled to more power than we believe is being afforded us.

Holding the Strength power perspective our internal and external running narrative may be that marginalized groups should “Stop complaining and acting like victims” or “Be willing to work harder.” An ongoing narrative may be that “The real issue is ‘reverse discrimination.’”

Strength—Our Leveraging Work

A primary learning edge, challenge, and opportunity of this power perspective is to leverage/integrate/utilize, from Oneness, the reality that we are all human and all share a desire for personal human dignity. This learning requires that we make the criteria for choices consciously non-violent to others as well as to ourselves and to our own group. It requires that we learn that these choices can be made despite long held narratives, rules, and laws that we must stay within, solely connected to, and solely value our own group.

A secondary learning edge, challenge, and opportunity of this power perspective is to leverage/integrate/utilize Sensitivity to explore a wider range of vulnerable emotions, exploring how to tolerate and utilize the ambiguity, unknowns, and uncertainty of oscillating between living within and beyond our own groups. We must develop tools that help us learn to recognize our rage, and our underlying fears and experience of threat, and where these come from. We can then begin to soften (distinguishing this from being overpowered), breathe more deeply, and find and make more non-violent room for ourselves and others.

Through leveraging Sensitivity, we must also begin to release our resistance to sociocultural difference, exploring our expansion into difference. In this way we begin to recognize our human commonality. We begin to acknowledge our impact on others through exposure to differences that feel manageable. We can find this challenging, but must learn to recognize when we are becoming overwhelmed prior to moving to/reverting to a defensive/defended position.

Relationship to Difference: Evaluation

Law: Survival of the Fittest

Safety Comes From: Ferocious courage and will

Identity: Protector

Truth: Whatever protects ones own

Body Location: Gut

Archetypal Representation: Warrior

ONENESS

Those of us who predominantly hold the power perspective of Oneness tend to devalue difference. We recognize and value our common humanity as the priority, and often hold the belief that this perspective is the path to ending violence and suffering in the world. We may feel certain that spending more time being aware of similarities and acknowledging our shared human goodness is the path to ending the troubles of the world. Thus, we over-emphasize our commonality believing that recognizing and acknowledging (let alone valuing) differences is misguided, divisive, and even dangerous.

From this power perspective, we tend to believe that we are welcoming to people of all backgrounds and are confused when that intent does not land as such. We may view ourselves as embodying love, care, kindness, compassion, and openness. We are often unaware that, in our focus on commonality, we are only welcoming those who are in the majority with regard to number and/or those from socioculturally privileged locations. We resist exploring ways our institutional/structural privilege impacts others and ourselves. Thus, when we are encouraged to acknowledge sociocultural difference and its impacts, we tend to respond with disbelief of its existence and/or significance. We will often encourage assimilation by those who are different from individuals in socioculturally privileged locations, including ourselves. This serves to communicate that all can be present as long as they are not too different. We will tend to strongly discourage recognition and discussion of the connections between power and diverse sociocultural locations.

Our focus on commonality in this power perspective may lead us to require that individuals around us have the appearance of “getting along” with each other. This can result in feelings and expressions of anger, conflict, confusion, and disagreement being unacceptable. Ironically, being “nice” and contributing to what may appear to be politeness, equanimity, and peacefulness may stifle the very conflict, interrogation, and disruption of power differentials that can lead to the authentic relationships, communities, and organizations that we often seek when holding this power perspective.

Oneness Day In and Day Out

The ongoing experience of this power perspective may be feelings of confusion, frustration, and even bewilderment that being caring and treating others compassionately could bring up concerns about diversity, fairness, and power. These feelings, however, may be tamped down and outside of our own awareness. Indeed, in institutions, individuals are most often expected to tamp down challenging emotions, and may even be held accountable for creating an “unsafe” environment if they are perceived as not doing so. This occurs because the majority of people hold the power perspective of Oneness and this perspective is institutionalized in most mainstream organizations, policies, procedures, publications, etc. This makes Oneness deeply reproductive. In other words, institutions are both a reflection of the Oneness power perspective and they recreate, model, teach and insist on compliance with Oneness.

Holding the Oneness power perspective our internal and external running narrative may be “I don’t see color [disability, religious difference, socioeconomic class, etc.]–I just see people” or “It’s more important that we focus on our commonality than on our differences,” or “We can all get along together as long as we treat each other with respect,” or “I wish that our LGBTQI, students would understand how welcome they are here.”

Oneness—Our Leveraging Work

A learning edge, challenge, and opportunity of Oneness is to leverage/integrate/utilize Sensitivity. Our growth is to become aware of our sociocultural identities related to power, privilege, and supremacy and how those identities developed. We begin to notice, witness, and acknowledge diverse sociocultural perspectives. We recognize how we may oppress our own structurally marginalized locations, and those of others, through shame, judgment, avoidance, and participation in oppressive systems. We begin to gain access to unacknowledged anger about, and fears of difference and develop tools for managing these feelings.

Another learning edge, challenge, and opportunity of this power perspective is to leverage/integrate/utilize Strength without the assumption of superiority and subordination. We may also utilize Strength to build capacity to contact and utilize challenging emotions, transforming them for increased capacity to explore and stay connected in the complexity of sociocultural difference within and between us.

Relationship to Difference: Devaluation

Law: Golden Rule (treat other the way you would like to be treated)

Safety Comes From: Focus on oneness

Identity: Diplomat/Peacemaker

Truth: Whatever avoids conflict

Body Location: Heart

Archetypal Representation: Lover